International airline emissions will be capped…some day

Climate pollution from international flights will come under regulation during the 2020s, according to an agreement adopted last week by the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization. The scheme aims to cap net emissions at 2020 levels by requiring carriers to purchase offsets for any pollution above that benchmark. The agreement drew criticism for its reliance on offsets and the slow pace of its implementation: it begins as a voluntary arrangement in 2021, and doesn’t become mandatory until the late 2020s. The plan closes a significant loophole in the Paris climate accords, which last week surpassed their ratification threshold for approval but do not apply to international flights, responsible for 60 percent of air travel and 2 percent of climate pollution. Biofuels for aviation are becoming available in small quantities, but are receiving little investment and are hampered by the low price of oil.

How are power markets like comedy? It’s all timing

As variable renewable power such as wind and solar play a larger role on the grid, the ability to time-shift power consumption will become more important—not just for customers to keep their bills low in the face of time-of-use rates, but also to match the load to the supply of carbon-free electricity. A California-based air-conditioning firm has developed a home-scale air-conditioning unit with a built-in ice-maker, which enables it to make ice when electricity is abundant, and use it to cool the house for at least three compressor-free hours. Unlike a battery, the ice tank will store just as much energy in 20 years as it does when new. New storage projects are in the news all over, including a 10-MW battery coupled to a Southern California Edison gas turbine; a multi-kilowatt flywheel that will store four hours of power for Hawaiian Electric; and a proposed 393-MW pumped hydro project in southern Oregon’s Klamath basin that faces opposition from local tribes.

Thin Green Line throttles oil train proposal

“Keep it in the ground” won two victories last week, as Shell Oil withdrew its proposal to build a 60,000-barrel-per-day oil-by-rail terminal at its Anacortes, WA refinery, and San Luis Obispo, CA rejected a rail terminal proposed by Phillips 66. Shell ascribed its decision to the sour economic climate facing petroleum, a claim met with skepticism by the project’s opponents. In Spokane, a city councilman mulled a ballot initiative to ban oil shipments through the city, unless the cargo’s pressure and flammability were reduced to meet safety criteria. A federal appeals court rejected the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s bid for an injunction to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline—a ruling that will allow work to proceed on private land, even as the Obama administration continues its moratorium on federal land.

The need to go negative

Handing off a livable planet to future generations will require extracting some carbon dioxide from the air, according to a new paper by James Hansen and colleagues. The paper, released in draft form for public review, finds that even with a quick transition away from fossil fuels, 72 ppm of CO2—or 570 billion tons—would have to be removed from the air to achieve the safe level of 350 ppm overall. Unbridled emissions growth would require future generations to remove more than 10 times that much. One place that carbon could go: agricultural soils, where improved practices could store billions of tons, the goal of a new federal interagency effort. Farming practices are important on the methane front, too: new research suggests recent increases in global methane emissions have come not from fossil fuel operations, but from livestock, rice paddies, and other wetlands.

EVs star at Paris show, earn German imprimatur

Following on the flashy roll-out of new electric vehicles at the Paris Motor Show last week, one of Germany’s two legislative chambers called for the EU to ban the sale of new gas and diesel autos by 2030. The move comes as a new study shows the cost per mile of owning and driving an EV is on par with internal-combustion cars, and recent indicators show an uptick in US interest in EVs. But if car prognosticators are right, future automobilists might neither own cars nor drive them, as car-sharing and autonomous vehicles take hold—a trend that General Motors’ CEO is anticipating. In a new survey, 70 percent of Americans polled said they are ready to try a self-driving car.

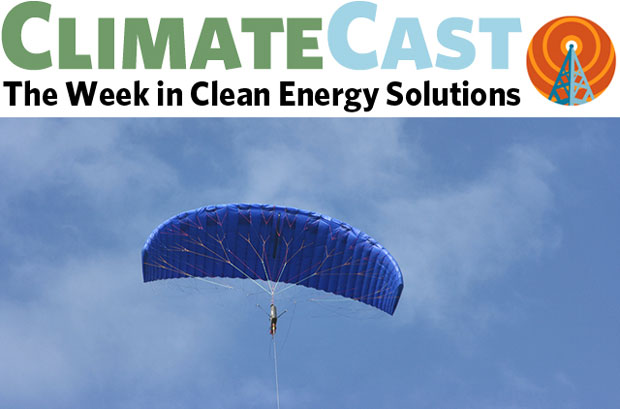

Let’s go fly a kite, up to the highest height

The growth of wind power in rural areas has thrown a financial lifeline to economically embattled farmers, according to Bloomberg Businessweek. Lease payments to Colorado and Iowa farmers enable them to avoid selling off parcels of land, especially when crop prices are down. These benefits accrue to less affluent regions: 70 percent of wind capacity is installed in counties below the median average national income, and property taxes from wind farms provide millions for local schools and other services. Offshore, the US Department of Energy envisions 22 GW of wind by 2030, at a price of 9 to 10 cents per kWh. In Scotland, a 500-kW wind project will generate power by letting the wind fly kites into the sky, spinning a ground-mounted turbine as they’re hoisted skyward.

In brief: LEDs meet legalized marijuana

As marijuana legalization spreads, with five more states deciding the issue on next month’s ballot, electricity demand for indoor growing has become more significant; it already comprises more than 2 percent of Denver’s electricity use in cannabis-friendly Colorado. New advances in LEDs—already used in Japan and Taiwan to raise vegetables in giant warehouses—can cut growers’ lighting bill in half and save even more on ventilation and cooling costs.

Image: This kite generates power as the wind lofts it into the Scottish sky. Photo © Kite Power Solutions Ltd 2015.