If extreme heat doesn’t freak you out about climate change, your brain may have melted

Only a few years ago, it was quite rare to see news weather coverage linking extreme storms or heat waves to climate change. That’s certainly no longer the case (although some TV stations have faced pushback from conservative viewers who object to news about global warming). This year’s dramatic and destructive weather of wildfires, storms, and flooding—including the Earth’s hottest four days in recorded history—has ensured that climate-weather connections are headline news worldwide.

The New York Times asks whether we have arrived at a “new normal” of daily climate disasters, including flooding, tornadoes, and dangerous heat. “It’s worse than that,” climate scientist Michael Mann told MSNBC’s Katy Tur—“what we are seeing is an ever-moving baseline of climate impacts…this only gets worse and worse if we continue to burn fossil fuels” that inject carbon pollution into the atmosphere. This year’s convergence of the periodic El Niño phenomenon and climate change, a situation other scientists called “very unusual,” “worrying,” “terrifying, and “bonkers,” has brought record land and sea temperatures that are, in turn, producing a largely unprecedented intensity of storms, wildfires, and flooding, in many cases simply overwhelming local preparedness measures. “There is no question that this cacophony was caused by climate change,” according to scientists cited by the Washington Post, “or that it will continue to intensify as the planet warms.”

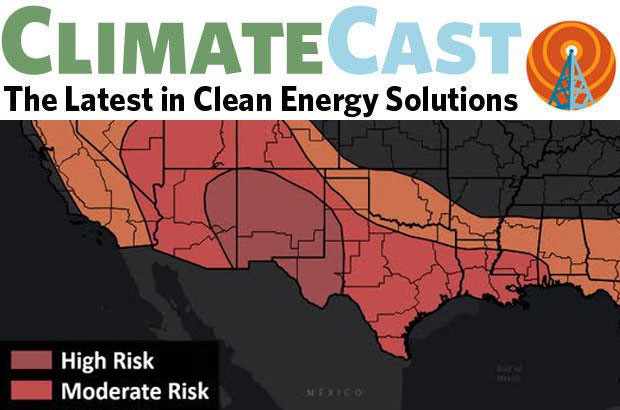

In Vermont, catastrophic flooding this week is revealing the limits of existing climate adaptation measures; more insurance companies are simply giving up providing flood insurance to new customers in Florida, California, and other states exposed to rising sea levels. In Arizona, heat conditions are so extreme that people collapsing on hot pavement risk second-degree burns or death. Researchers project that extreme heat will cost the US $1 billion in heat care costs this summer alone. Meanwhile, scientists warn that the worst of this year’s climate impacts are likely yet to come.

What does this all mean for the clear imperative to accelerate clean energy solutions to the climate crisis? Los Angeles Times journalist Sammy Roth took this week’s heat wave as an opportunity to consider how we think and talk about climate threats and solutions.

Gas money and oily influence

The oil and gas industries continue to exert their influence in attempts to maximize profits and blunt the impact of climate and clean energy policies in our region and elsewhere. Northwest energy utility Avista Corporation is suing the state of Oregon in an effort to abolish the state's Climate Protection Program (CPP). Adding insult to injury, Avista is maneuvering to force Oregon customers to bankroll the utility’s political activities while simultaneously increasing Washington subscriber gas rates by an average of 9.8% since January 2020. David Pomerantz of the New York Times highlights similar tactics being employed by gas and oil companies across the country. The fossil fuel industry's shady behavior has also been making waves internationally, as industry lobbyists stand accused of obfuscating their affiliations and motives during previous United Nations Climate Change Conferences. As COP28 draws near (yes, there really have been 27 of these to date), a bloc of climate activists are pressuring conference organizers to require that oil and gas industry lobbyists clearly identify themselves as such during the upcoming summit, to be held in the petroleum-rich United Arab Emirates.

New climate goals—but not rules—for global maritime shipping

The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations' global shipping regulatory agency, met last week to establish “net-zero” goals for the shipping industry by 2050. Currently, global shipping accounts for 3% of yearly worldwide carbon emissions, comparable to Germany’s annual carbon emissions. One of the technologies that was championed as a solution is hydrogen fuel cells. This system doesn't rely on combustion to generate electricity and is more efficient for energy production per pound than conventional fossil fuels currently used in the shipping industry. The resulting agreement has come under attack because of its non-committal language: “by or around, i.e., close to 2050, taking into account different national circumstances.” Countries agreed to near-term “checkpoints,” a 30% emission cut by 2030 and an 80% cut by 2040. Current IMO Secretary-General Kitack Lim called the agreement “monumental” and said “it is in many ways a starting point for the work that needs to intensify even more over the years and decades ahead of us.” This meeting also dealt a blow to Loss and Damages, a fund that affluent nations agreed to set up at last year’s COP27 conference to help poorer nations suffering the brunt of climate impacts. French President Emanuel Macron failed to convince a majority that carbon taxes on shipping were a good mechanism to finance the fund.

🎧 What we’re listening to

Our new feature, What We’re Listening To, highlights a podcast episode or longer-form radio interview that we found compelling.

This week we are listening to a podcast by Ezra Klein from the New York Times, “This Taught Me a Lot About How Decarbonization is Really Going.” Robinson Meyer is the guest of this episode. He founded Heatmap, a publication focused on climate and energy transition.

This discussion demystifies some of the complex dynamics inside the Inflation Reduction Act, breaking down the many ways it is being applied and could be applied to advance the green energy transition for the United States. They speak on the clash between energy infrastructure investments and the environment, the complexities of permitting, and red states stand to double their IRA investments compared to blue states.