Consider a class of new technologies, just emerging into the mass market, whose widespread adoption would make obsolete a vast segment of the country’s economic infrastructure.

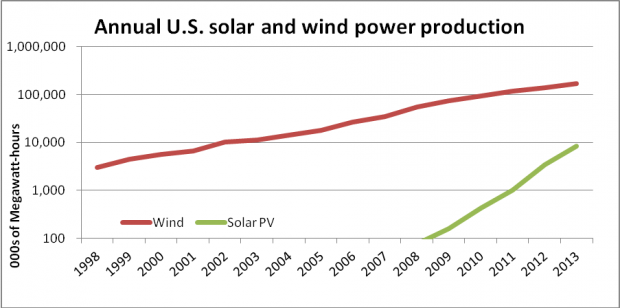

The nation’s electric grid has seen a meteoric rise in renewable generation in the last 15 years, which offers a useful lesson in what it will take to continue down the path to a completely carbon-free power system.

Renewable electricity has been growing so fast that the only way to grasp it visually is with a logarithmic graph, where each tick-mark on the vertical axis represents a tenfold increase over the previous one. Think of it like a Richter scale, where a 7 delivers 10 times more motion than a 6. And, like the Richter scale, it’s measuring a seismic shift.

Source: DOE EIA's Electric Power Annual for 1998-2004, Electric Power Monthly for 2004-1013

In the last 20 years, we’ve seen smaller sectors upended by technological shifts—video rental shops, recorded music, newspapers. Anyone still remember stenographers and telegrams? But to find a technological transformation that shook every corner of the economy, you have to go back to the early days of the automobile.

Like solar and wind power, automobiles had a long period of technological incubation before they appeared on the market in any significant numbers. The first vehicle powered by internal combustion was built in 1863, and yet in 1900, U.S. auto production was still only 4,000 cars.

Over the next dozen years, however, consumers embraced the automobile slightly quicker than wind generation has been growing (taking 12 years for their production to grow as much as wind generation did in the last 14), but not nearly as fast as solar (which increased as much in only four years).

(Source: Historical Statistics of the United States, U.S. Census Bureau)

Even after automobiles entered mass production, it took time for them to supplant animal-powered transportation. Auto traffic didn’t exceed horse-drawn traffic in New York City until 1912, and 1913 was the first year when more cars were manufactured in the U.S. than wagons and carriages.

To get there, early adopters of the automobile had to surmount the entrenched attitudes of people who thought only in terms of animal-powered transportation. Britain’s 19th century Red Flag Law obliged drivers to keep to a speed limit of 4 mph, and walk at least 20 yards ahead of the motorcar with a red flag to alert riders and teamsters of the approaching vehicle. It remained in force for more than 30 years.

In the United States, the first auto race in 1895 couldn’t proceed until Chicago suspended its ban on motor vehicles on city streets, and some American cities and towns barred motor vehicles well into the first decade of the 20th century.

These attempts to hold back the tide of automobility have their modern-day equivalent in the fossil-fuel industry’s crusade to hobble the growth of renewables. The Koch brothers and several power companies have funded the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) to lead a campaign against two state policies favorable to green energy: renewable portfolio standards, which tell utilities to obtain a minimum percentage of green power, and net metering, which saves consumers the full retail price of electricity for any kilowatt-hours they generate on their rooftops. ALEC is tracking 42 state-level bills that would weaken those renewable-friendly policies.

These political battles are crucial because the skyrocketing growth in clean energy isn’t due to technological improvement alone. It’s been helped by landmark policies, starting with the 1980 law requiring utilities to buy power from independent producers. More recently, tax credits for clean energy production, and renewable portfolio standards have given the industry further momentum.

That pump-priming has paid off. Production volumes have increased, bringing prices down to near-parity with grid-generated electricity. The experience gained in the early years of wind farms led to improved design and reliability. And, like the automobile assembly line (introduced for the Model T in 1913), economies of scale have cut costs, which in turn bred greater demand.

Just how fast have prices dropped? In the last five years, the average cost for utilities to buy solar power has fallen by a factor of four, now just above 5 cents per kilowatt-hour. These prices reflect a 30 percent investment tax credit to developers, which means that the true cost is around 8 cents.

In the graph below, prepared by scientists at Lawrence Berkeley Labs, the size of the circle represents the amount of power generated by a solar project; the center of the circle corresponds with the price.

Cost of solar Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) to utilities

If the recent rate of cost-cutting continues for a few more years, solar will reach parity with its fossil competitors even before taxes. In light of this trend, Barclays’ Credit last week downgraded electric utility bonds because they can see that inexpensive solar power could shake the foundations of the utilities’ business model.

These trends shed new light on the so-called “stranded assets” problem—economics-speak for the fact that 80 percent of the fossil fuel reserves on the books of major oil and coal producers must be left in the ground to keep the planet’s overall warming below 2 degrees Celsius.

Instead, those reserves, worth tens of trillions of dollars at today’s prices, would have to be written off for the greater good. The Nation’s Christopher Hayes compared the fossil firms’ resistance to that of slave-owners fighting abolition: freeing the slaves was too great a hit to plantation balance sheets for them to accept it without a fight.

Considering the headway that renewables are making in electricity markets, a moral decision to protect the climate isn’t the only reason that fossil-fuel reserves might become stranded assets. The fear that solar and wind will make fossil fuels obsolete is Big Carbon’s worst economic nightmare.

That said, we can’t count on trend becoming destiny. Imagine if the equine transportation lobby had had the cynical politics of Karl Rove, the concentrated wealth of the Koch brothers and other members of the coal-and-oil oligopoly, and the twisted megaphone of Fox News: the rise of the automobile might have been delayed by decades. (While that might sound bucolic to drivers sitting in 21st-century traffic jams, it would have been less appealing to inhabitants of the horse-manure-clogged cities in 1900.)

We can’t sit back and leave it to engineers and entrepreneurs to bring prices down and volumes up, because the vested interests of the fossil industry are arrayed against them.

Instead, it will take the added power of people demanding that state legislators and utility commissioners write rules of the road to get us to a carbon-free future—rules that maintain fair access to the grid for consumers who generate their own power, that invest in applied research, and that put a price on carbon commensurate with the damage it does to our climate.

With that kind of political wind in its sails, renewable energy will sweep fossil reserves into the dustbin of outmoded assets like rotary phones and livery stables.